Before Gaza — there was Biafra.

The first time I heard about Biafra, I was as a child growing up in southwestern Nigeria. I remember hearing fragmented stories and tales that sounded distant, they were almost unbelievable. I never truly grasped the weight of it all until I read Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie years later.

With time, I came to understand that the Biafran War was far more than a regional or ethnic conflict. It was one of the first wars ever broadcast on television. A war that brought the haunting images of hunger, starvation, and despair into living rooms around the world.

The horror of Biafra gave birth to a new global consciousness, one that redefined how the world responds to human suffering. This facilitated how modern humanitarian activism was forged and also the founding of major international NGOs like Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) and Concern Worldwide, the Biafran War became a catalyst for the birth of organized humanitarian intervention in Nigeria.

This article argues that the Biafran War fundamentally transformed humanitarian engagement in Nigeria and, in turn, the world. It analyzes how the global visibility of the war’s unprecedented suffering compelled responses from major powers and spurred the creation of new international NGOs. Finally, it assesses how this legacy of intervention and advocacy continues to influence the humanitarian principles and practices of today.

Historical Background

The 1967–1970 Nigerian Civil War pitted federal troops against the secessionist Republic of Biafra in the country’s southeast. When Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu declared Biafra’s independence on May 30, 1967, Nigeria descended into a brutal conflict that would claim over a million lives. The federal government’s military blockade of the region cut off food and medical supplies, creating one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 20th century.

By mid-1968 which was the peak of the war, the world was watching. Images of starving Biafran children filled television screens and newspaper covers across Europe and America, igniting outrage and heartbreak. It was one of the first wars ever televised, one nation split into two by conflict where mass hunger and starvation became a weapon and the camera became a witness.

Historians often describe it as the moment when the global conscience was awakened to African suffering, turning Biafra into a “cause célèbre” for journalists, missionaries, and ordinary citizens who felt compelled to act.

Yet beneath the humanitarian outcry, global politics played a defining role. The Cold War loomed large over the conflict. The United States maintained a position of official neutrality, largely deferring to the United Kingdom, its close ally and Nigeria’s former colonial power, which firmly supported the federal government. The Soviet Union, too, backed Nigeria with military aid, eager to assert its influence on the African continent.

On the other side, France extended moral and logistical support to Biafra, driven by both humanitarian sympathy and strategic interest in countering Anglo-Saxon dominance in Africa. China, positioning itself as an anti-imperialist ally of liberation movements, expressed rhetorical support for Biafra but offered little tangible assistance.

In the middle of this geopolitical chess game stood ordinary people, millions of civilians facing hunger, displacement, and death. Out of the world’s horror came action: churches, missionaries, and newly forming humanitarian groups stepped in to fill the gap left by cautious governments. This was when seeds of modern humanitarian activism in Nigeria were sown, albeit amid the chaos of war and the silence of politics.

International Response and Relief Efforts (1967–1970)

After Biafra declared independence in May 1967, the federal government moved to isolate the region and the humanitarian consequences were immediate and catastrophic. The federal blockade of food and medicine supplies was rapidly followed by an outbreak of hunger and diseases. Images of children looking like skeletons in feeding centres, exhausted mothers, and overflowing refugee camps quickly made the conflict a global humanitarian emergency.

The Bystander Effect: Governments and Diplomats

British parliamentary records show the political edge of these alignments. Debating arms and assistance, Members of Parliament recorded that there had been different government attitudes and even supplies from external states, a dynamic that complicated Western governments’ ability to act solely on humanitarian grounds.

In 1968, Lord Brockway of the UK Parliament stated his displeasure at the lack of a response from Britain after 8 months of war. He further noted that there should be more advocacy for peace and ending the war.

In his statement, he noted a surprising coalition of suppliers: “There has been a coalition between France and Portugal which have supplied arms to the East, Biafra. Not only has the British Government continued to supply …”

While the United States took a cautious, largely neutral stance as a way of being conscious of its ties to Britain and wary of appearing to impose a settlement, U.S. agencies and civil-society groups still played important humanitarian roles. An example of this is the USAID providing relief after many dilemmas due to the urgency of the situation.

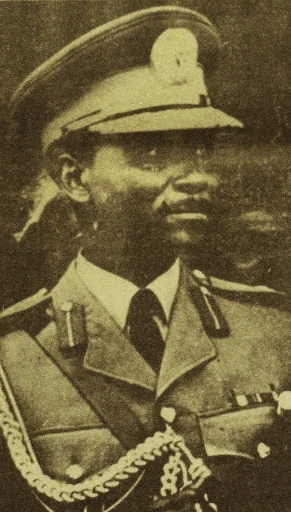

The USAID in a bid to save face and also respond to the crisis while maintaining neutrality provided relief mechanisms for both sides of the war. But the ultimate goal was ending the war and General Yakubu Gowon made his stance clear in 1970.

“Only a cease-fire will halt the starvation of an estimated 5–6 million in Biafra.” General Yakubu Gowon, from ASC Leiden – Rietveld Collection – Nigeria 1970 – 1973 – 01 – 093 New Nigerian newspaper page 7 January 1970. End of the Nigerian civil war with Biafra (1970-1973) | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

Humanitarian Action Outside State Control

Where States hesitated, churches, volunteer coalitions, and NGOs moved quickly. Scandinavian and other European church groups, British charities (Oxfam, Save the Children), Catholic Relief Services and a constellation of smaller religious and secular groups organised sea and air shipments into the Biafran region.

The most dramatic example was the Biafran airlift: where supplies were shipped to staging points such as São Tomé and flown secretly into Biafra. One operational review records the scale and daring of these missions: tens of thousands of tons were delivered by thousands of flights, a lifeline that operated outside formal diplomatic channels.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) also mounted a major relief operation under extraordinary constraints; its work in Nigeria exposed logistical and political limits that would later prompt reforms in how the ICRC managed large scale civil-war relief. However, they were also faced with many challenges as noted in their review below.

The plight of “hundreds of thousands of civilians, including women and children, is going from bad to worse,” and the organisation struggled with fuel, access, and the dangers of crossing combat zones

The humanitarian response to Biafra was notable not only for its scale, but for its moral tenor. Many aid workers who went into Biafra returned convinced that neutral silence was inadequate. Bernard Kouchner — a French doctor who later became a co-founder of Médecins Sans Frontières — captured this change in attitude in a candid reflection on his Biafra experience:

I was a perjurer. Upon my return [from Biafra] to France… I formed a committee against genocide in Biafra. My reasoning was simple. I did not want to repeat the mistake of the ICRC, which, during the 1939–1945 war, had not condemned the Nazi extermination camps. That was the origin of Médecins Sans Frontières and Médecins du Monde.”

The Post-War Transformation (1970s–2000s)

When the guns fell silent in January 1970 and Biafra surrendered, “Nigeria” emerged victorious but deeply fractured. The humanitarian machinery that had mobilized during the war airlifts, church coalitions, medical missions, and Red Cross networks did not simply disappear. Instead, these wartime operations evolved into the framework for a permanent humanitarian presence across Nigeria.

International organizations that had first entered through emergency relief began to professionalize and institutionalize their operations. Oxfam, which had coordinated relief convoys during the blockade, expanded its mandate to include post-war rehabilitation, agricultural support, and community development programs in Eastern Nigeria. Similarly, Save the Children, initially focused on feeding programs, established long term child welfare initiatives that laid the groundwork for its modern day Nigeria office.

A pivotal institutional outcome of Biafra was the birth of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in 1971. French doctors returning from Biafra, disillusioned by the limitations imposed by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), founded MSF on the principle of témoignage — “bearing witness.”

MSF’s creation symbolized a new era of humanitarianism that combined medical intervention with moral advocacy. The legacy of Biafra thus stretched far beyond Nigeria’s borders, inspiring a global rethinking of humanitarian ethics and organizational independence.

By the turn of the 21st century, Nigeria had become not just a recipient of aid but a regional hub for humanitarian coordination in West Africa. Many of the NGOs that had once delivered food by night flights into Biafra were now training Nigerian professionals, shaping policy, and advocating for global humanitarian standards.

The trajectory from crisis relief to institutionalized activism reflected a profound transformation: the tragedy of Biafra gave rise to a sustained humanitarian consciousness — one embedded in both international norms and Nigerian civic identity.

Nigeria’s Role as a Humanitarian Hub

Within Nigeria, the postwar decades saw a gradual but steady evolution. What began as foreign-led relief movement matured into a vibrant domestic humanitarian ecosystem. Nigeria became both a recipient and a regional driver of aid coordination in West Africa.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, international organizations such as the UNHCR, MSF, Oxfam, and CRS had established permanent offices in Lagos and Abuja, often training Nigerian professionals who would later found their own NGOs. This localization created a feedback loop: global expertise flowed into Nigerian society, while local actors brought context, legitimacy, and cultural understanding to humanitarian work.

Biafra’s greatest contribution may be conceptual rather than material. It shifted global humanitarianism from Charity based relief to Rights based advocacy. Relief was no longer seen as an act of pity, but as an obligation rooted in justice and human dignity.

This shift influenced the rise of global humanitarian norms — such as the principles of “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) and the integration of human rights frameworks into humanitarian work. As historian Alex de Waal writes in Famine Crimes, “Biafra was the crucible in which the modern humanitarian conscience was forged.”

Final Thoughts

More than fifty years later, the Nigeria Civil war remains both a scar and a symbol. It taught the world that images can move nations, that neutrality has limits, and that humanitarian silence can be complicity. It also taught Nigeria the enduring value of solidarity, organization, and civic action.

The war’s humanitarian legacy exists every time a volunteer distributes food in a flood-prone community, a local NGO advocates for internally displaced persons, or a journalist bears witness to injustice. The spirit that began in 1967 in the midst of hunger, isolation, and despair continues to define humanitarian engagement in Nigeria today.